How Defoe comes to write his novel and why he creates the Female Picaro

Daniel Defoe’s ‘Moll Flanders’ is the story of a woman who we see grow overtime, allowing the reader to choose their own opinions as Defoe subverts the narrative form and challenges the audiences’ expectations with regards to how we as a society should punish criminals.

With thanks to The Literature Online, I was able to read Defoe’s take on punishment and how the convicted begin their mental journey of penitence and arbitration.

In ‘Moll Flanders’, we see Defoe disrupt the narrative standard with sensational tales of exploits as we see Moll struggle as a child (perhaps in accordance with Demetz’s ‘Young Culprits’ theory) but soon grow towards temptation, eventually robbing a child and suffering the consequences, perhaps an ironic fate considering Defoe ‘depicted ordinary people as victims of their circumstances’ (Watt, P 94). How being affected as a child has not allowed her to learn from her experience and reflect on what she might do.

The reader, however, is left feeling not necessarily confused but leaves the story with a complex emotion towards Moll. As previously mentioned, she grows from a girl with poverty into a woman with wealth. ‘I brought over with me for the use of our plantation … the gift of the kindest and tenderest child that ever woman had’ (Defoe, Chapter 68). We may even feel a sense of heroinism; a past rags-to-riches story if you will for our picaro. On the other hand, however, we feel morally ambiguous towards Moll. There is no real redemption arc or much sense of atonement. ‘I never brought myself to any sense of my being a miserable sinner,’ ‘My poor afflicted governess … more truly penitent’ (Defoe, Chapter 57).

The reader feels both a sense of pride and frustration at Moll Flanders, making her a challenge to the reader’s expectations.

Defoe himself had had a grudge with how the law was presented by the state. Perhaps this is why we feel ambiguously frustrated towards Moll.

Born in 1660, he grew up in a time of political/social instability and had always seen himself as more of a philanthropist and a man of the people.

As a committed Christian, he always supported religious freedom and freedom of the press including fighting for Monmouth’s Rebellion – a Protestant uprising against the new Catholic King, James II.

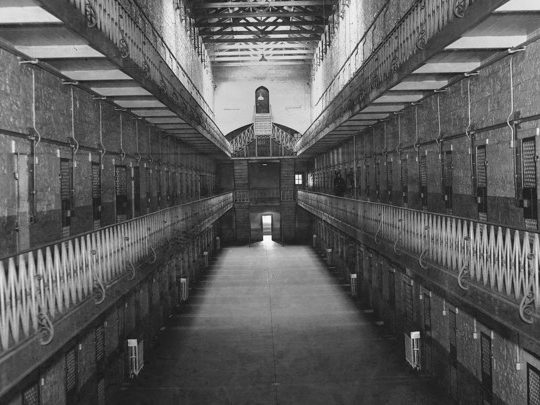

It was, however, when in 1702 that Defoe was punished for seditious libel (the crime of making public statements that threaten to undermine respect for the government, laws, or public officials) after publishing a pamphlet titled ‘The Shortest-Way with the Dissenters; Or, Proposals for the Establishment of the Church’ landed him in Newgate Prison in London, England. The language Defoe uses is ultimately defaming of the throne and portrays themes resembling that of regicidal uproar to inspire the masses. ‘And now, they find their Day is over! their power gone! and the throne of this nation possessed by a Royal, English, true, and ever constant member of, and friend to, the Church of England!’ (Defoe, 1702).

Whilst in the gaol, however, Defoe remained adamant about his feelings towards the state. He wrote ‘Hymn to a Pillory’ which was sold in the streets, declaring he was ‘an example made/To make Men of their honesty afraid’.

It is this statement which provides an understanding into how Moll Flanders feels towards the end of the novel. How her confessions perhaps do not equate that of justice and being free of sin within the context of the novel.

Bibliography

(Defoe, Daniel, ‘The Fortunes and Misfotunes of the Famous Moll Flanders, United Kingdom, 1722, William Rufus Chetwood)

(Defoe, Daniel, ‘The Shortest-Way with the Dissenters; Or, Proposals for the Establishment of the Church’, London, England, 1702, https://www.bartleby.com/27/12.html).

Images courtesy of:

Dr. Jaap Harskamp, ‘Daniel Defoe’s Moll Flanders: the Flemish Collection’, January 18th 2017, (Site Accessed 5th December 2019) https://europeancollections.wordpress.com/2017/01/18/defoes-moll-flanders-the-flemish-connection/ (Original Copy of Moll Flanders)

Peter Berthoud, ‘A Grim View from Inside Newgate Prison in the 1890s’, 29th May 2019, (Site Accessed 5th December 2019), http://www.peterberthoud.co.uk/blog/16022016135217-a-grim-view-inside-newgate-prison-in-the-1890s/ (Newgate Prison)

Reginald P.C Mutter, ‘Daniel Defoe’, April 20th 2019, Encyclopedia Britannica Inc., (Site Accessed 5th December 2019), https://www.britannica.com/biography/Daniel-Defoe (Daniel Defoe Engraving)